Cornell researchers have unearthed precise, microscopic clues to where magma is stored, offering scientists—and government officials in populated areas—a way to better assess the risk of volcanic eruptions.

The new research was published Feb. 8 in Science Advances.

In recent years, scientists have used satellite imagery, earthquake data and GPS to search for ground deformation near active volcanoes, but those techniques can be inaccurate in locating the depth of magma storage. By finding microscopic, carbon dioxide-rich fluids encased in cooled volcanic crystals, scientists can determine accurately, within one hundred meters, where magma is located.

“A fundamental question is where magma is stored in Earth’s crust and mantle,” said lead author Esteban Gazel, the Charles N. Mellowes Professor in Engineering, in Cornell Engineering. “That location matters because you can gauge the risk of an eruption by pinpointing the specific location of magma, instead of other signals like hydrothermal system of a volcano.”

Gazel said speed and precision are essential. “We’re demonstrating the enormous potential of this improved technique in terms of its rapidity and unprecedented accuracy,” he said. “We can produce data within days of the samples arriving from a site, which provides better, near real-time results.”

In volcanic events, magma reaches the Earth’s surface and it erupts as lava and—depending on how much gas it contains—it could be explosive in nature. When deposited as part of the fallout of the eruption, fragmented fine-grained material—called tephra—can be collected and quickly evaluated.

Gazel and doctoral student Kyle Dayton, the first author of the paper, “Deep Magma Storage During the 2021 La Palma Eruption,” deduced how to use inclusions of carbon dioxide-rich fluids trapped within olivine crystals to precisely indicate depth, as the carbon dioxide density of these inclusions is controlled by pressure.

These fluids can be measured quickly using a calibrated Raman spectroscopy instrument to determine—in terms of kilometers—how far down the magma was stored and the depth of the scorching reservoir.

More precise Raman spectroscopy methods were developed in the Gazel lab. “We improved the precision by an order of magnitude from available geobarometers, from kilometers to meters,” he said, “but also the spatial resolution of inclusion measurements from tens of microns, down to one micron compared to previously available microthermometry techniques.”

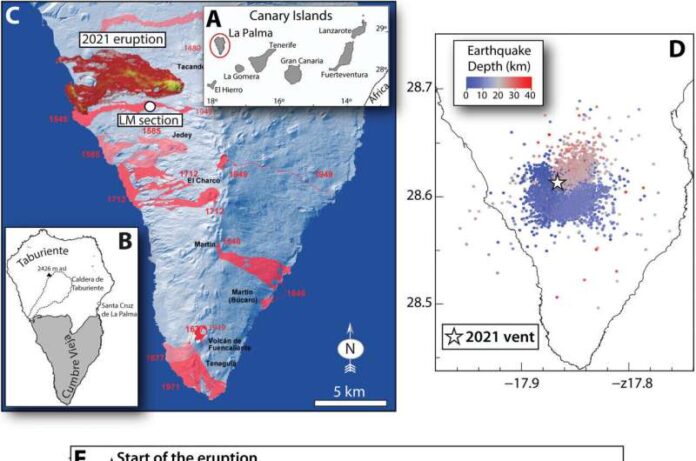

After five decades of dormancy, new vents in the Cumbre Vieja volcano on La Palma in the Canary Islands opened and began erupting Sept. 19, 2021. Weeks later, Gazel and Dayton joined a small, elite team of international researchers to study the volcano.

This Canary Islands research led to Gazel and Dayton to pick through tephra to find crystals, which in turn provide data to improve eruption models and forecasts.

“We’re finding how deep magma is stored before an eruption through what the volcano brings up,” Dayton said.

“As these volcanic crystals grow, they occasionally, accidentally trap little bubbles of carbon dioxide fluid,” she said. “These crystals get exhumed during the volcanic eruption and we search the tephra and look for crystals containing fluid inclusions. Through these tiny accidents we can uncover some of Earth’s volcanic secrets from the deep to better understand and prepare for future eruptions.”

More information: Kyle Dayton et al, Deep magma storage during the 2021 La Palma eruption, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ade7641

Journal information: Science Advances.

Provided by Cornell University.